Since you are reading this, I assume you are competent at your job. Good for you!

We all admire people who “get results” — the type of people who always seem to achieve their personal goals or the goals of their organizations — and regard them as supremely competent. Usually this admiration is perfectly apt. Think of a baseball star who consistently launches home runs, the kind whose value used to be measured by appearances on Wheaties boxes.

But what if that is not enough. In fact, what if the “getting results” is despite or even the consequence of abject failure. Think of a baseball star who slams home runs but relies on drugs to do so. We deride such a player as a fraud and disgrace. Or one who hits home runs but leads the league in strikeouts and errors and commands the lowest batting average. No Wheaties for you!

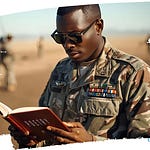

True competence is an overall achievement, not a matter of a few data points clustered around specific categories. It is one of the greatest fallacies in leadership that value is achieved simply by reaching a goal. How you get there, why you want to get there, and what else you do along the way matter.

In an essay entitled “Don’t Do Good by Doing Bad,” I have already addressed the issue of the ends not justifying the means in decision making, including a handy three-part test for the rare occasions when they just might.

So how does this concept play out in our assessment of performance and leadership?

Simply put, failure is failure, even when it results in a visible win. To begin, we need to distinguish failure from mistake. An individual mistake is a setback, an error that can usually be corrected and/or learned from. Mistakes are inevitable and can even be beneficial if they become the impetus for improvement. For this to happen, first acknowledge the mistake and then try to understand it. Doing so requires temerity and can take some fortitude. Once it is understood, can it be fixed? What lessons can be derived from it? Finally, fix it if possible and learn from it no matter what.

In the workplace and in life, mistakes are moment-by-moment occurrences. An employee forgets a meeting, or a boss forgets to send an email. These individual incidents are often no big deal in the grand scheme, but sometimes the consequences are considerable, such as when an employee misses an important deadline or the boss misreads the budget numbers. In a healthy workplace, everyone — including and especially the boss — can and will readily acknowledge mistakes so that everyone can help fix them and learn from them. If a mistake, though, is the result of a more endemic problem, something that is easily avoidable and too often repeated, it is probably a failure.

The nature of failure is more fundamental to the person or institution. It is systemic. Like a mistake, failure can sometimes be fixed and can certainly be learned from, but failure, being fundamental, is frequently overlooked or concealed and, after being acknowledged, requires fundamental reform.

An all-too common failure is the failure of a boss to foster a healthy workplace to begin with. A workplace where employees are not free to admit mistakes or in which the boss does no wrong is a failed workplace. It does not matter if the workplace seems productive. Just as a baseball player who can hit home runs but is otherwise useless would be considered substandard (or a designated hitter in the American League), a boss who relies on concealment and deception to succeed is definitionally incompetent.

The worst workplace failures stem from those who are most powerful and influential — bosses and star or favorite employees — but who intimidate, belittle, and bully others. They imagine their status and ability to produce put them in a separate class with license to behave as they please. Bob Sutton’s critical work The No Asshole Rule exposes the fallacy of their thinking. Sutton cites studies that show the broadly deleterious effect of “assholes” in work environments, including when those jerks are star performers.

The classic case involves a super salesman who lords his prowess over his colleagues. His employer knows he is bad for morale and a horrible human, but look at his numbers! How can I get rid of such an amazing salesman? Sutton demonstrates that removing that salesman from the workplace would, in fact, increase overall productivity and more than offset his lost sales numbers.

In other words, whatever his sales success, by being a jerk, the super salesman’s behavior suppresses aggregate numbers and is detrimental to the workplace. He is, therefore, incompetent. The boss, by the way, is also incompetent for keeping the jerk around and allowing him to lower productivity. Simple.

If you have ever seen the David Mamet play Glengarry Glen Ross or the 1992 movie made from it, you will have a ready example of the harm workplace jerks can do. They are incompetent.

In baseball and other sports, the ruinous effect of star jerks is well known. Teams avoid otherwise productive players who are “bad clubhouse guys” because they know such jerks reduce team spirit and team success.

The Dunning-Kruger effect suggests that the incompetent tend to overrate their abilities. After all, not everyone can be above average. It is, therefore, axiomatic that those who question their own competence in order to improve are often quite capable. The rule is, if you think you are wonderfully competent, you probably are not. On the other hand, if you doubt your competence and strive to excel, you are probably sufficiently competent or at least on the path to competence.

Mistakes, by contrast, are not necessarily a sign of incompetence in themselves. The failure to address mistakes, on the other hand, is. When a boss fails to address the frequent and systemic commission of errors, that boss is, by definition, incompetent. When a boss bullies or harasses others or does not protect others from bullies and harassers, that boss is a failure no matter what the numbers say. Don’t be that boss. New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo offers a contemporaneous and pertinent object lesson as he resigns from office. The proverbial “getting results” ain’t all that. Process matters, and a proven and sound system will always yield the best and most consistent results. Everything else is failure.

Share your thoughts on this topic or participate in a discussion by leaving a comment below or by contacting me directly by email:

You must register with Substack to leave a comment, which stinks but is painless and risk free.

I look forward to hearing from you.

Post this essay on social media or send it by email to someone you want to inspire/bother.

Subscribe to receive my weekly newsletter and special editions directly to your mailbox.

You can improve your ability to achieve your organization’s mission.

Visit my website and reach out to me to learn how.