“Yet ev’ry distance is not near”: Bob Dylan Schools Us on Distance

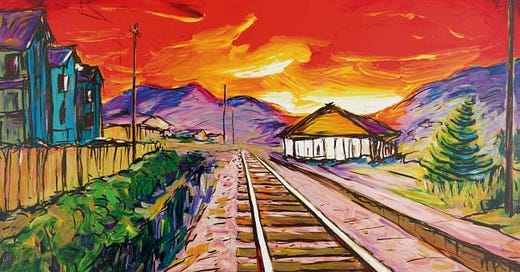

Bob Dylan, Train Tracks 2019--Dylan's numerous visual studies of train tracks disappearing to a vanishing point signify his intense interest in distance and perspective.

Anyone who knows me even a little knows that I am, um, somewhat enthusiastic about the work of a certain singer-songwriter named Bob Dylan. Yes. I am something of a Dylantante.

One of the many things I admire about Dylan is his ability to take conventional phrasing and views and convert them into a truly sui generis perspective. My recent post on nostalgia suggested that we often soften our view of the past much as the coarse surface of a stone seems to soften as we move away from it. It is an obvious comparison, but it put me in mind of some Dylan observations regarding distance that are, shall we say, counterintuitive, which naturally delights me.

The mid-eighties production standards of Dylan’s song “Tight Connection to My Heart (Has Anyone Seen My Love)" muddies the recording and has limited its appeal, but the lyrics are superb. In the last verse before the final chorus, he tells us of the beating of a man in a “powder-blue wig” who is later “shot / For resisting arrest.” At the very end of the verse he states flatly,

What looks large from a distance

Close up ain’t never that big

This could strike you as a bland non sequitur or a cleverly inverted profundity since we usually perceive something at a distance, say a traffic tunnel, as far smaller than it is. (Yes, junior, our big car will fit through that little tunnel.) In truth, though, the lines are a commentary on the incidental nature of most outrages. Dylan’s trick is to reverse the chronological order of the episode by introducing the concept of distance before the “Close up” event that proceeds it.

You may quibble with Dylan here. I may quibble with him, for that matter. Perhaps an example is in order. We are all aware of the death of George Floyd at the hands of police officers and the fact that video of that slow-motion murder sparked or re-sparked a massive national uprising and shifted public opinion. Applying Dylan’s take demonstrates that while Floyd’s murder loomed large in the public eye, for those experiencing it at the time, perhaps even for Floyd himself, it was just a series of discrete moments and decisions that culminated in homicidal tragedy. Floyd certainly sensed he was dying, but his cries for help (including, movingly, to his late mother) suggest that he held out hope that the police would relent or that there would be an intervention. In other words, he did not accept the inevitability of his circumstances because they were not inevitable. Any number of things could have prevented his death, from the mundane to the sublime. That none of them did was unforeseeable in that present, and any inevitability we sense in such a drastic scene is only imposed in hindsight.

I cannot know for sure what the experience was like for Floyd, his murderers, or his witnesses on the scene, of course, but that is how I read the situation. To Dylan’s point, as horrible and huge as that incident--what a shockingly inadequate word--as that catastrophe must have been for those present, not one of them, not even Floyd himself, could ever know how immense it would become for our nation. His homicide, unlike the tunnel that the car (or train) approaches, as monumental as it is up close, is even larger in the distance. In the song, the man in the powder-blue wig dies, also at the hand of the police, but in that moment no one could predict how substantial the atrocity, real or imagined, would become by being enshrined in Dylan's song. In other words, the act of witnessing or participating in such an abomination cannot indicate with any precision how significant such an event might become to those who are removed in time or space from it.

To be clear, my intent is not to diminish the murder of George Floyd by comparison to the fate of a likely fictional Dylan character but to demonstrate how his death led to and became something beyond all expectation. Would Floyd have chosen to die if he could know of the movement his death would inspire? Would anyone? W.B. Yeats ponders a similar conundrum at the end of "Leda and the Swan," which describes another violent catastrophe with vast repercussions:

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

As I said, I have quibbles with Dylan's lyrical claim. Plenty of disasters take place in anonymity. If not for the viral video, Floyd’s murder would likely have faded from public consciousness if it ever even made it to public consciousness, and the impact of its aftermath may very well have shrunken over time and across distance as so often happens. Instead, now it is an important highlight of the historical record of our day at the very least.

For his part, Dylan's philosophy of time and perspective remains remarkably consistent across decades. Nearly twenty years after recording "Tight Connection," Dylan closed his movie Masked and Anonymous with a voice-over monologue in which he asserts,

The way we look at the world is the way we really are. See it from a fair garden and everything looks cheerful. Climb to a higher plateau and you'll see plunder and murder.

As with the doctrine of perspective he sketches in “Tight Connection,” this statement seems to upend our normal point of view. Isn’t it usually that the forest looks chaotic and confusing when you are in its midst but calm and orderly from a mountaintop above? No, in this monologue and in keeping with the lines from his song from the eighties, Dylan again suggests that distance can lead to greater insight, context, and understanding. By the way, this the exact reverse of the more conventional philosophy of perspective that Jonathan Swift utilizes in Gulliver's first two voyages.

The January 6th insurrection at the Capitol offers a perfect example of Dylan's philosophy at work. Several who participated later claimed that they were just swept up with the crowd and had no intention of entering the building let alone rioting. They speak of their experience as though they regarded themselves as unwelcome visitors on an unofficial tour, nothing more. They imagined that they were there as much to see the sights as to shout slogans. Like the mere tourists they feigned to be, they even took selfies with police and stayed inside the guide ropes. Step back to a distance (physical or temporal), and we can see that their mere attendance, no matter their intent, ensures that they contributed to the havoc. Their profession of unawareness does not exculpate them from the charge that they willingly joined a mob that committed acts of destruction, injury, homicide, and sedition. For these folks, though, it may very well have seemed just a particularly rowdy tour group at the time. Nonetheless, consider that one of the people who died during that attack was trampled by the mob. Anyone who was part of that unlawful crowd, whether they were in attendance in that moment or not, is culpable for her death because their presence alone contributed to the overall size of the mob and subsequently the stampede. There can be no mob to trample her if there are no people to create a mob, so every member of that mob is complicit in her death as they are in all the day's consequent deaths, injuries, and terror.

Interestingly, both of Dylan’s examples—a killing by police and “plunder and murder”—feature violence and occur at the end of the two works in which they appear. As always, there is a consistent thread in Dylan's art. In the movie monologue, the “fair garden” evokes Eden, and even the adjective “fair” seems archaic and vaguely biblical. The vicious disorder he describes evokes end times, which has long been a Dylan preoccupation. Even his 1980ish deep dive into christianity centered on a church that promotes an "inaugurated eschatology" with an apocalyptic bent. It is not surprising, then that Dylan would expand his view from a narrow focus on Eden to a wide-angle on a world of brutality and mayhem as if to suggest that we exist in a bubble or garden of false security. Prepare for a decline, all ye who bask in contentment! In fact, the sentence before this passage in the movie monologue uses the phrase “things fall apart,” from Yeats’ poem “The Second Coming,” which itself is eschatological in theme:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned

I am not recommending that we stock up on bottled water, power bars, and duct tape to prepare for end times, no matter what Dylan’s view on the subject is. But there are useful lessons we can draw from Dylan’s insight into distance, perspective, and perception in these two quotes.

Down to the Brass Staples

This blog is supposed to be primarily about management and leadership, so let me roll it around to that domain. If you are a boss, or even if you are not, it is important to be aware that your day-to-day, moment-to-moment choices and actions potentially have a larger effect on the future than you may expect. It is not just the cumulative effect of such decisions, but each one, no matter how small, could itself become enormous in its implications and impact. Think about it. An overlooked staple can wreak havoc on the inner workings of an office copy machine just as an inappropriate or insensitive comment could blow up into legal action or even termination.

One may be tempted to affect an attitude of sustained hyper-vigilance to forestall unwanted consequences, but this approach is neither practical nor ultimately effective. A general awareness though that one’s small actions can loom large in the future is in order. I admit that my truism here should seem boringly obvious, and yet how often is its objective veracity still overlooked or downplayed?

The only readily workable solution to the dilemma of unintended consequences is to identify your core principles and, if they are sound, stick to them. Be decent whenever possible. There is that word again, decent. Simply assure that you consistently work with integrity, and you will be largely protected from negative ramifications or at least will be prepared to address and counter them. Stick to your principles, and at they end of the day the consequences will be yours to own honestly. And always remember, as the bard says,

What looks large from a distance

Close up ain’t never that big.

A brief photographic study of Dylan's philosophy of distance and perspective