You have no doubt heard the hoary story of the blind men who encounter an elephant for the first time. Due to their limited powers of perception, the men, touching different parts of the elephant, each reach radically different conclusions about the nature of this creature. (I cite this tale with apologies to the visually impaired, who are generally no less nor more insightful than the visually encumbered.)

The point though is that we primarily take in only what we discern and have a limited capacity to project beyond that. Plato makes a similar case in his Allegory of the Cave in which humans can see only shadows of reality but not reality itself. We primarily know only what we take in, and it can be hard to project into the unknown with any accuracy. We too often want to believe that what we see is all there is to get.

This is the stuff of science and philosophy and art. Think of all the novels and movies that focus on the limits of perception. If you have seen any of The Matrix franchise, you know what I mean. In the original movie and its sequels and spinoffs, humanity is trapped in a computer simulation that synthesizes daily existence. Only those few who have been freed can perceive this mass enslavement and experience the grit and grime of really real reality.

In the Matrix universe, if you are offered a choice of two pills, select the red one, and you will be freed.

In fact, adherents to Qanon and other such conspiracy theories refer to understanding their version of the truth as “red-pilling.” The implication, of course, is that most of us are not aware of the conspiratorial truth behind what we perceive and that the truly true truth is accessible only through viewing certain YouTube videos, participating in rightwing chat rooms, and listening to the My Pillow guy. You just have to be open to it.1

The fact remains, though, that the truth is not fully accessible no matter how many dietary supplements you purchase from InfoWars. Sure, art and philosophy and religion and science lay claim to some knowledge of truth or of the Truth, but none of these noble pursuits has an absolute handle on what is real. And only one of them ever claims otherwise. Even in The Matrix, taking the red pill may expose the unreality of one type of perception, but it also launches you into a whole other reality with its own limits of perception (see Plato).

My point is that it is hard to grasp the truth. Part of the problem is the limitation of our brains. Truth is big, bigger than our capacity to grasp. But more significantly, we are hampered by the limits of our perception.

Think of walking down a sidewalk. Absent a camera or well-placed mirror, we cannot see around the corner of that brick building up ahead. For all we know, that turn in the sidewalk does not resolve into existence until the moment we reach it. Perhaps, solipsists may speculate, reality does not occur until the instant you perceive it. You see a tabletop, but its underside is nonexistent unless you run your hand there. I think I saw something like this on the Twilight Zone.

Silly stuff, but it is how we purport to know. If there is a tabletop, I surmise from experience that there must be an underside. I may have an image of it in my mind or a memory if I have seen it, but the current state of its existence is perfectly irrelevant to my experience of eating my meal properly from the top side.

Our brains may not be large enough to grasp the totality of reality, but they are large enough to fill in the gaps. For instance, scientists tell us that sight is not one solid and continuous view of an image but serial images that our brain stitches together into a stable whole, and of course our eyes see everything upside down. It is our brain that compensates by flipping the image.

This one benefit is enough for me to declare that I am very pro-brain.

But what if our brain goes too far? What if, in compensating for the limits of perception, we fill in the gaps by imagining fictions? Frankly, we do this all the time. We worry about a future we cannot foresee, the future being the most unknowable unknown. We see phantoms when none exists. In dealing with others, we ascribe intention when we have no way to be sure. Speculation is useful. It can prepare us and protect us, but it can also deceive and mislead us.

This is where all those conspiracy theories come from. They overcompensate for our lack of knowing. There is something comforting in thinking that there is an order to what seems chaotic and out of control even when that order is imposed by a malevolent force. Such order gives us something to act for or against. Chaos is harder.

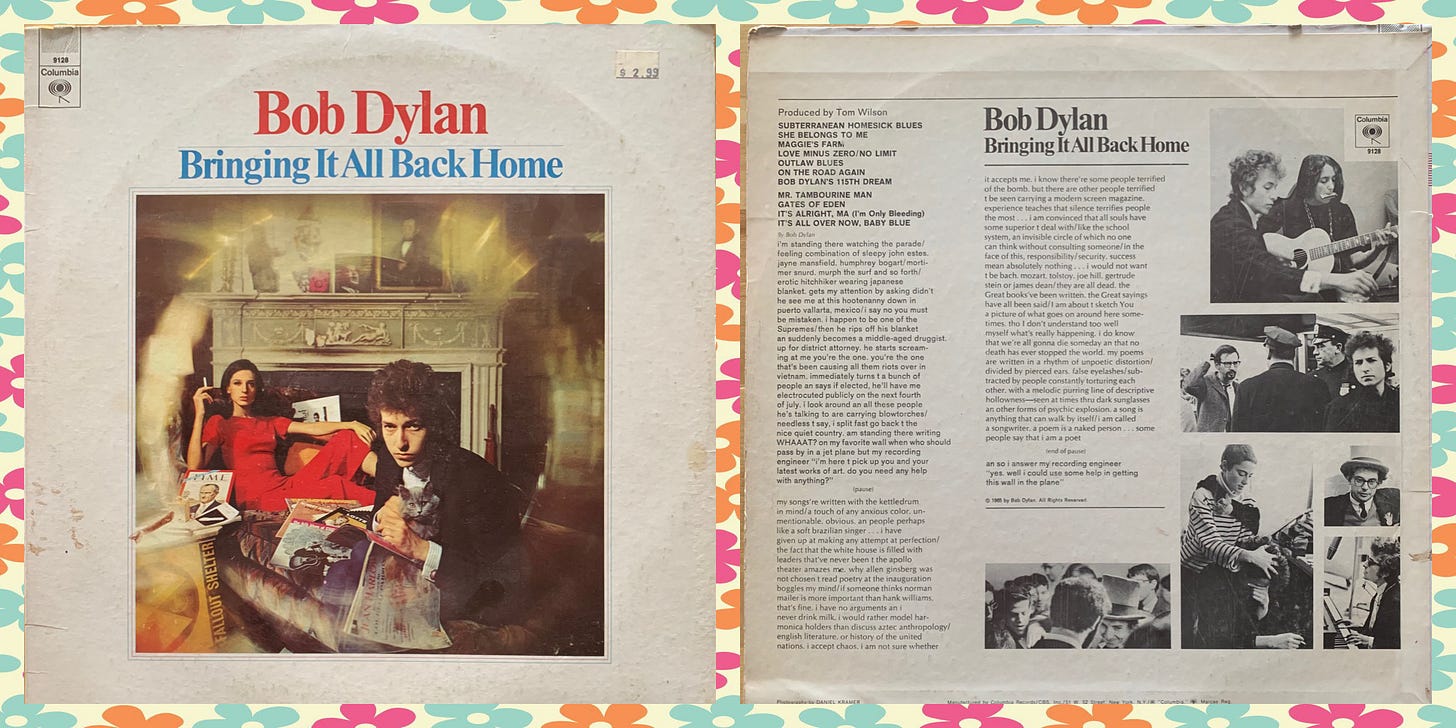

One of my favorite Bob Dylan quotes is not from a song but is from a long poem he wrote as album liner notes:

i accept chaos, I am not sure whether it accepts me.

By this he means, I think, that he acknowledges the general chaotic nature of the universe and our inability to perceive it, but he, as an artist, still will try to make sense of it. That is what artists do. That is what thinkers do. That is what everyone does to varying degrees and with whatever success. And that is what I am doing here.

We cannot fully understand the truth. We cannot fully grasp the chaos of the universe. We try, every moment just about, to understand, grasp, and even control it, though. Sometimes we are just plain wrong. Too often we overcompensate, missing the mark altogether because we want to believe something to be true even in the face of its inherent untruth.

All we are left with is the process. Not truth or the Truth, but the process of attempting to know and to understand. It is those very times when we are most sure we are right that it is an excellent idea to assume we are wrong. To check and double check so that we do not get sucked into some well-ordered cycle of self-replicating and self-promoting rerendering or rationalizing of the chaos.

That, there, is where madness lies, not in being caught up in chaos but in not accepting the chaos before trying to find sense in it.

After I had already drafted this essay, the excellent Hidden Brain podcast hosted by Shankar Vedantam covered some overlapping ground in an episode entitled “Useful Delusions.”

I am always struck at the number of conspiracy theories that closely track the plots, themes, and imagery of movies. Many of these conspiracy theories surmise and depend on the existence of technologies that only exist in science fiction, such as mind-controlling microchips.